I wanted to write this before I’ve been out longer than I’d been in. I agonized over my decision to leave the Air Force—largely because I experienced it as an issue of professional identity.

Why I joined

After wrestling at a high school math and science academy, I wanted to keep up physical fitness and develop leadership skills in a technical environment. I also needed financial assistance to fund college. I had Army, Marine, and Naval officers represented among my grandparents—but rather than inspiring any overwhelming patriotism in me, I think military lineage simply enabled me to consider the possibility of going military at all. I considered attending a military service academy but chose a more balanced experience with Air Force ROTC at the University of Virginia.

My initial desire to study mechanical engineering didn’t survive my intro computer science class, which so greatly captured my interest and imagination that I promptly switched majors. I most memorably took Defense Against the Dark Arts, a course that used computer security topics like viruses and vulnerable software to introduce core CS concepts like formal languages and computability theory. Professor Jack Davidson taught the class, and also supervised my thesis; Jack shortly afterward led team TECHx to take silver in DARPA’s Cyber Grand Challenge (CGC).

In the brief few months after graduating but before entering active duty, I worked remotely as a full-stack web developer for an iPhone app startup. I loved the work but had to put it down when the Air Force called.

How it went

I was mentally prepared1 to be thrust into a role as a communications officer responsible for managing a team of network technicians that keep the base online. Like most military officer roles, I’d require a bit of initial training to familiarize myself with any relevant subject matter before joining a communications squadron and shortly entering a supervisory position.

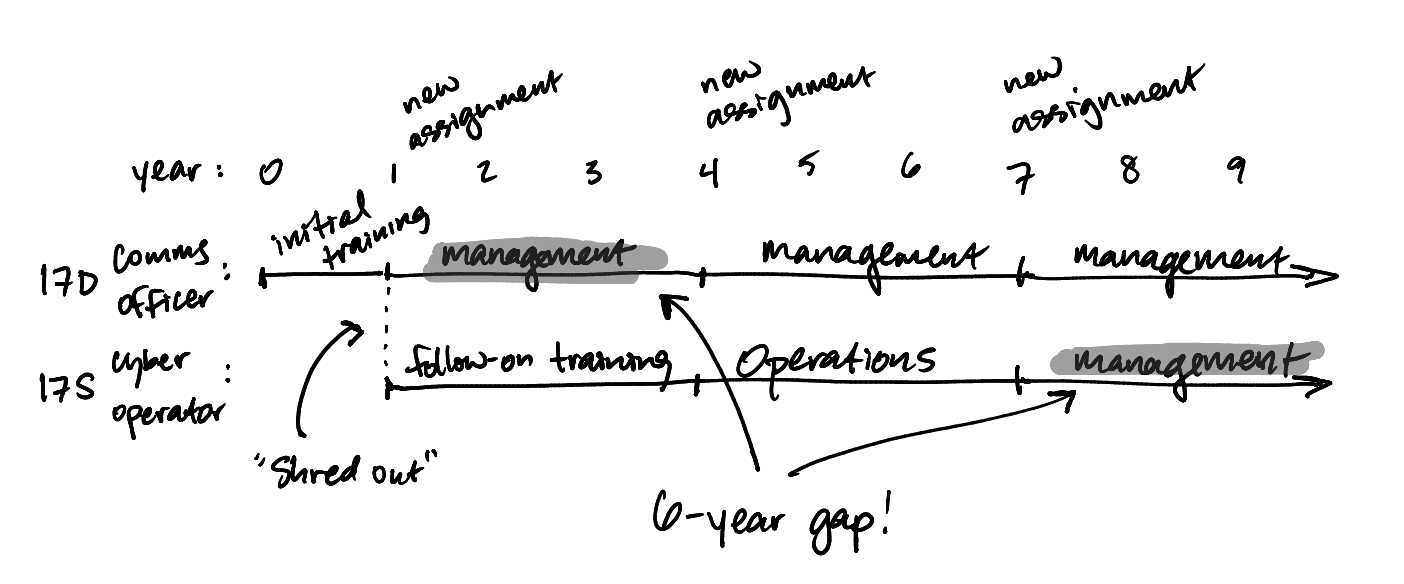

However, I performed well enough in that initial job training to be selected for follow-on offensive cyber operations training—namely RIOT, with a few courses before and after. This would be a nontraditional career path strongly divergent from the typical military officer experience. I paint with broad strokes in the illustration below; assignments can vary in duration, and “management” responsibility is obviously more nuanced than a single term can describe, but the big picture remains the same: communications officers (17D) follow a more traditional track toward early large-scope management, while cyber operators (17S) differ greatly, especially during the first narrowly focused years following initial training.

The years following my “shred out” to cyber operator were some of the most unexpected2, challenging, and rewarding experiences I could have hoped for. Even so, I began to struggle with the question: Am I a technician, or a leader? I hope the question surprises you. This wasn’t simply my own private musing—I was urged along with my peers on an accelerated path toward general management, and was subtly warned that it was unbecoming of an officer to cling too closely to technical responsibilities. In the end, I decided not to answer this falsely dichotomic question, and to (spoiler) leave the Air Force instead. There were several notable angles to this decision.

Leadership

I struggle with the idea that one can simply apply domain-agnostic leadership experience toward any problem area and expect quality results. It reeks of the idea that technical detail can be abstracted away to “just widgets.” In Changing the Cyber Warfare Leadership Paradigm, Eric Seligman described the current problematic practice of staffing USCYBERCOM with nontechnical leaders from outside the cyberspace domain, writing quite bluntly:

Imagine placing an officer who has never fired a rifle in charge of a Marine infantry company or platoon.

Beyond decision-making, I think the problems here also extend to morale. I understand that I work best under leaders that I aspire to be like. It’s hard to look forward to subsequent positions of higher responsibility when those roles are implicitly shown not to require technically qualifying experience.

Bureaucracy

The Air Force’s various management structures have been administatively optimized to fit an organization of over 320,000 people—several thousand of those being cyber personnel. The best representative example of this administrative burden is found in the annual performance report writing process, which requires summarizing a year’s worth of work in about a dozen bullet points, where each bullet takes a rigid “action; impact – result” format that can easily look something like this:

Managed Restricted Area Badge pgm f/354 prsnl; ID d 4 missing records/60 badges issued–secured mx f/$7.8B infra

The report must follow a wide assortment of other unintuitive rules and conventions. Most lamentably:

- Each bullet must take up exactly the full width of the text box on the report form

- Any shortened word must be on a list of approved abbreviations

- If a word is abbreviated once, every other instance of that word in the whole report must also be abbreviated in the same way—which, by side effect, changes the line length of any other affected bullets containing that word (see first point)

This circular process of massaging each bullet on a report can take multiple days just to write an initial draft, before being reviewed and perhaps rewritten by multiple levels of supervisors. It’s not unusual for the report to take upwards of six months to travel up and down the leadership chain and close out with all required approvals. As a manager, now multiply this by all the members of your team (including your own report), and the man-hours skyrocket.

I’m not necessarily suggesting that this process is unnecessary or ineffective; after all, the whole idea here is that a promotion board member should be able to glance (perhaps only for a few seconds) at a report before deciding whether or not to select an Airman for promotion. The same also applies to award packages.

Instead, I mean to call attention to this: A few well-meaning principles can be extrapolated so severely in a massive organization that you cannot recognize the original good principles at play. Such is the Air Force bullet.

Opportunity cost

I very regretfully turned down a three-year program called CNODP, the DoD’s premier vehicle for developing technical leaders in computer network exploitation. This was particularly painful since I’d dreamed of attending this program throughout my active duty career. While once-in-a-lifetime, CNODP came with an additonal three-year service commitment (six years total), and the Air Force made no guarantee that my next assignment would be relevant to CNO—so it felt like a gamble. That’d put me halfway to an enticing 20-year retirement, making it harder to get out even if I felt like it were the right decision.

Lifestyle

My firstborn was a month old when I left for a six-month training. Fortunately, he and my wife accompanied me for part of it, but I was absent for all daylight hours and my wife was alone in a temporary home with no support nearby. That’s hardly an unusual story for the military, and a relatively mild one at that—but it helped me appreciate and even long for proximity to friendship and family. Moving every three years makes that hard to come by.

Decision

In the end, my final question grew beyond “Technician or leader?” into “Should I adopt the Air Force’s problems as my own?” Should I stay in and become the kind of leader that I wanted to be led by? Perhaps it’s a bit presumptuous to suppose that I could even be that person. In any case, I felt it was too much to ask my growing family to hang on while I came home each evening stressed by the imposed professional dissonance I felt at work.

I got out with the aim of finding or building the kind of team that I’d want to work with. I did a bit of both.

Since leaving

I made an immediate clean break from government—no Reserve or Guard, and fully commercial work. I’m hardly lying when I say I just wanted to grow my hair out. I’ve also been able to work completely from home and get to see my wife and four kids intermittently throughout the day. It’s hard to overstate how much more available I am to my loved ones, spatially and emotionally.

While working in the private sector, I’ve come to understand that it has a special place for leaders who want to stay technical: it’s called the IC track, and its ladder largely mirrors the people management track in terms of scope of responsibility. Pat Kua’s Trident Model even breaks the IC track into leadership and execution components, where people spend 70–80% of their time:

- Management: leading and supporting people, managing structures and processes.

- Technical leadership: establishing vision, managing risk, clarifying requirements.

- “True” IC: executing with deep domain knowledge.

One could argue that this structure has some similarities to the military’s commissioned officer, warrant officer, and enlisted tracks. I think nuance makes this comparison murky—warrant officers can manage people, and senior enlisted members will often take broad leadership roles while leaving the “keyboard” behind—but it perhaps strengthens the case the Air Force’s yet-existent warrant officers in offensive cyber ops.

It sounds like things have gotten a bit better for Air Force hackers since I got out. Offensive cyber operators now expect back-to-back operational assignments after they finish training and certification. CNODP graduates expect a follow-on assignment relevant to CNO. Performance reports are trending toward narrative format instead of bullet points. Anecdotally, I’ve heard from still-active Air Force officer peers in cyber ops that they’ve been allowed to stay in “technical director” positions near the 10-year mark, without having to take on the usual administrative load. It appears3 that there’s an ongoing attempt to formally establish a technical track for officers all the way through O-6. All this despite the fact that the Air Force “does not directly track what work roles the 17S may fill in the personnel system of record.”4 That’s a dramatically different picture than the one I was presented with as a company grade officer, and I’m glad for it.

I’ve since spent time in IC, tech lead, and management roles. I think that the departure from government has helped me understand more clearly how much I enjoy people management. Far from “not wanting to be a leader,” it turns out that much of the (externally motivated) inner conflict I felt was due to the expectations of the commissioned officer career progression at the time. I don’t experience that tension anymore.

I have much to be thankful for. Beyond the unique experience I gained in the Air Force as an offensive cyber operator, I also learned how to brief an engaged audience; to ruthlessly debrief and get to the root cause of a problem; to write persuasively in a professional setting; and to recognize and extract the impact of my team’s accomplishments. I encountered a few outstanding leaders, one of whom told me pointedly:

Your job as a leader is to put your neck on the line for your team.

I’ve never forgotten that, and it’s meant more to me with time.

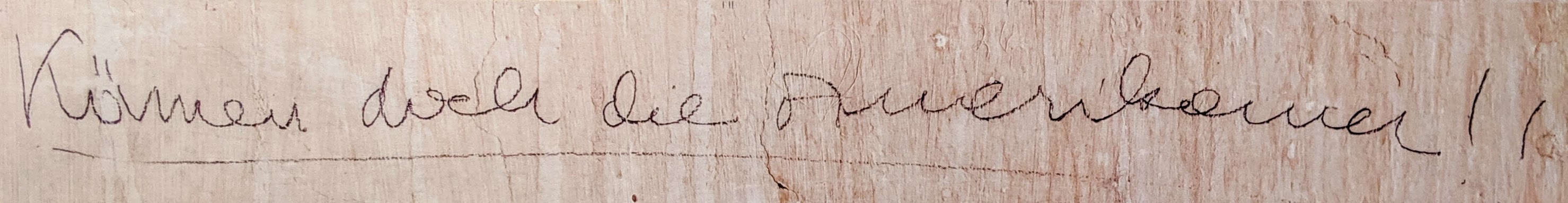

Shortly after getting out and still turning much of this over in my mind, I visited a friend stationed in Germany. I found “If only the Americans would arrive!” scratched on a wall in the basement of EL-DE Haus, a former Gestapo prison.

I swelled with sadness at imagining the prisoner who wrote those words, and also with pride at the heritage I realized I had in having been part of the U.S. military.

-

Before deciding to apply to become a cyber officer, I attended an extended training session with the Air Force’s STO community (think Navy Seals, but they can call in air strikes). Very cool, but I spent my evenings lying awake in my bunk thinking about the PiMac mod I’d left undone back at home. That sum moment of clarity finalized my decision to go cyber. ↩︎

-

I spent the better part of a year as a construction project manager. Very much a “wouldn’t have asked for it but glad it happened.” ↩︎

-

Highest quality RUMINT. ↩︎

-

Military Cyber Personnel: Opportunities Exist to Improve Service Obligation Guidance and Data Tracking, p. 23 (Dec 2022) ↩︎